HUMANITARIAN RESEARCH

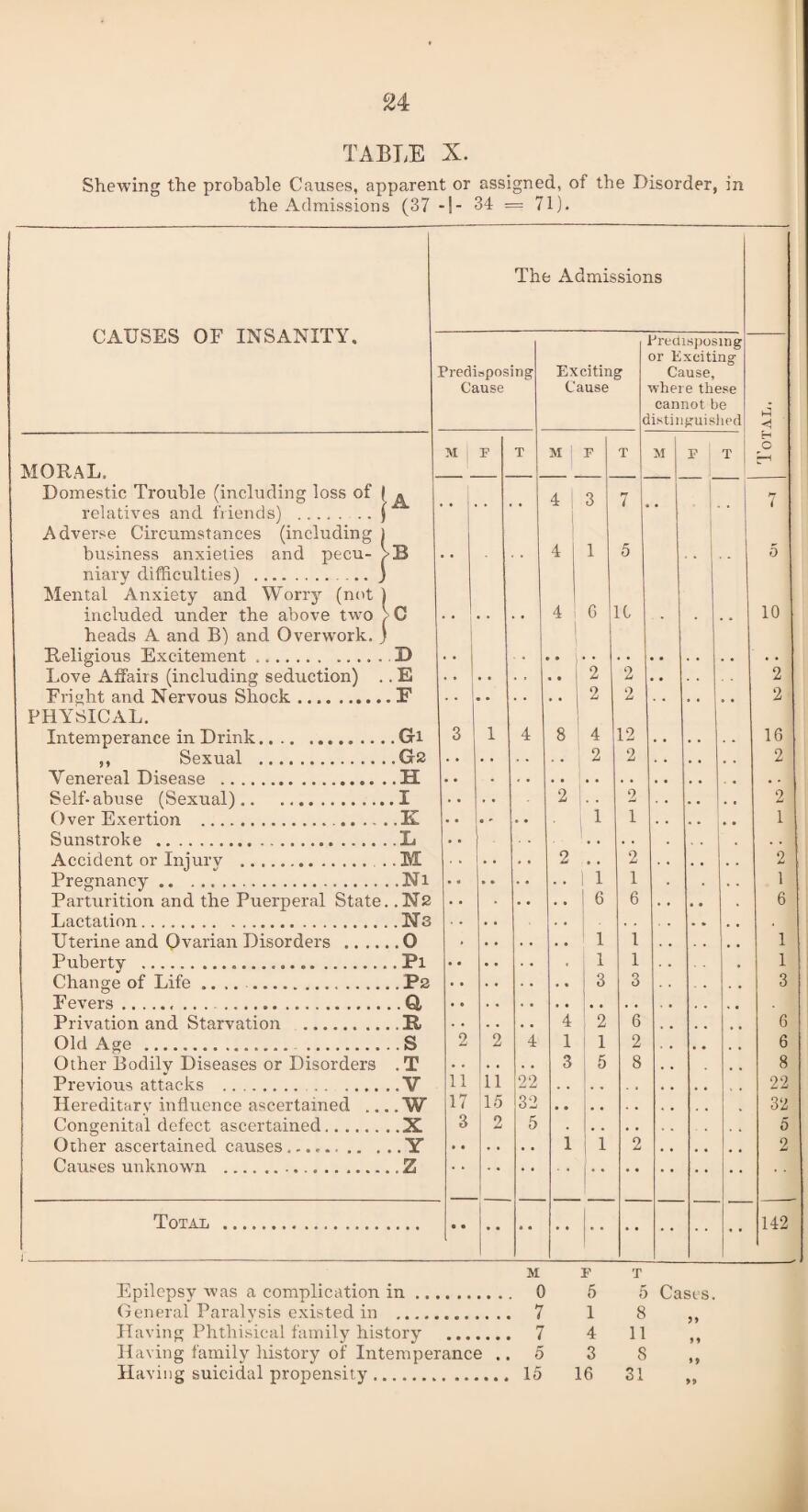

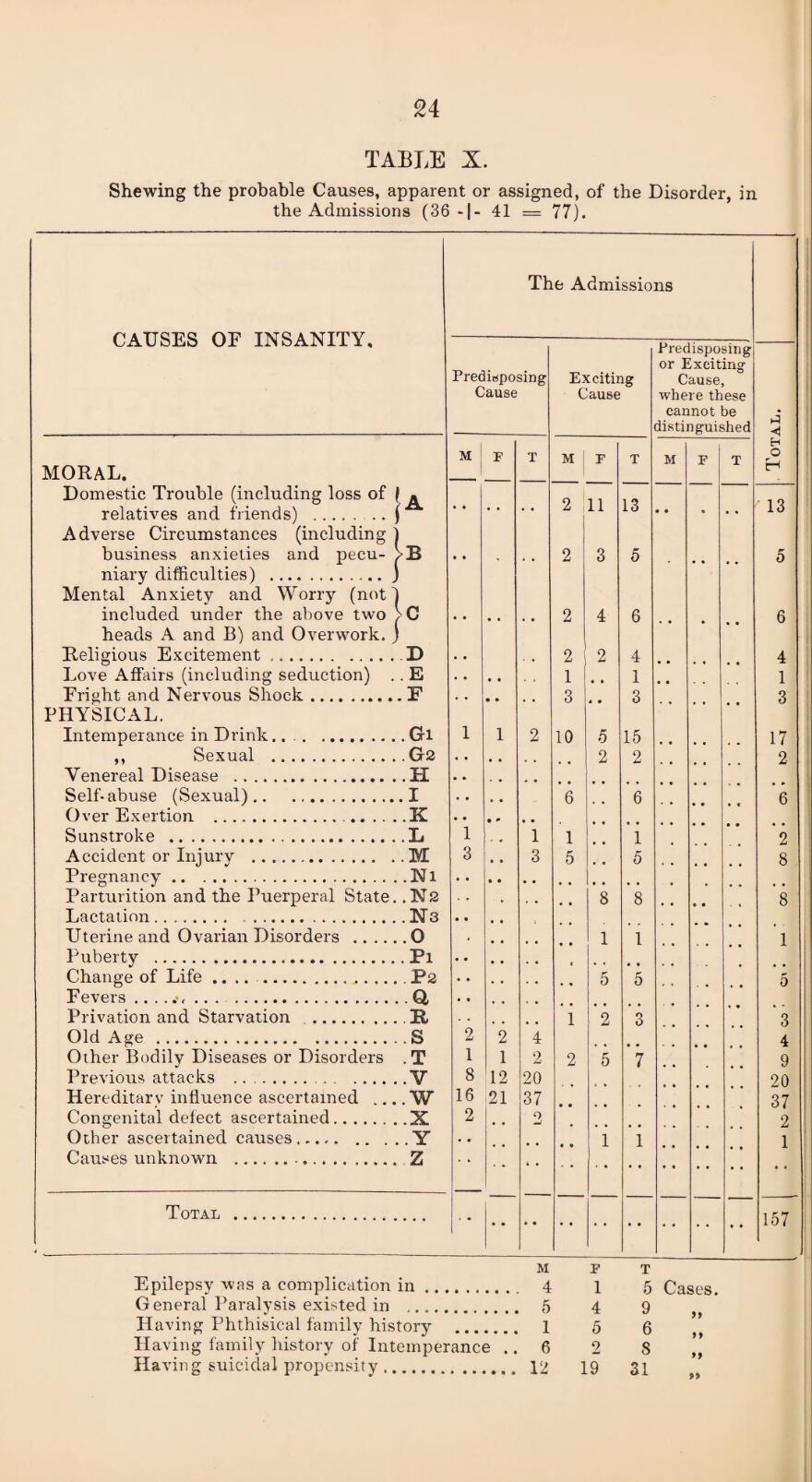

We have divided up much of our research into three categories: Gender, Class and Sexual Orientation; exploring the experiences of people admitted to asylums through identity, background and societal position within the context of the time. However, as you will notice, there are issues and themes which run throughout each of these categories, such as inequality and a lack of human rights. Although the treatment of patients in this period may seem alien and distant from modern day practice, it should be noted that the doctors and benefactors involved in the formation of the asylums, for the most part, wanted to advance treatments for patients and believed that the work they were doing was necessary and forward thinking in comparison to what came previously.

Treatment and the patient experience

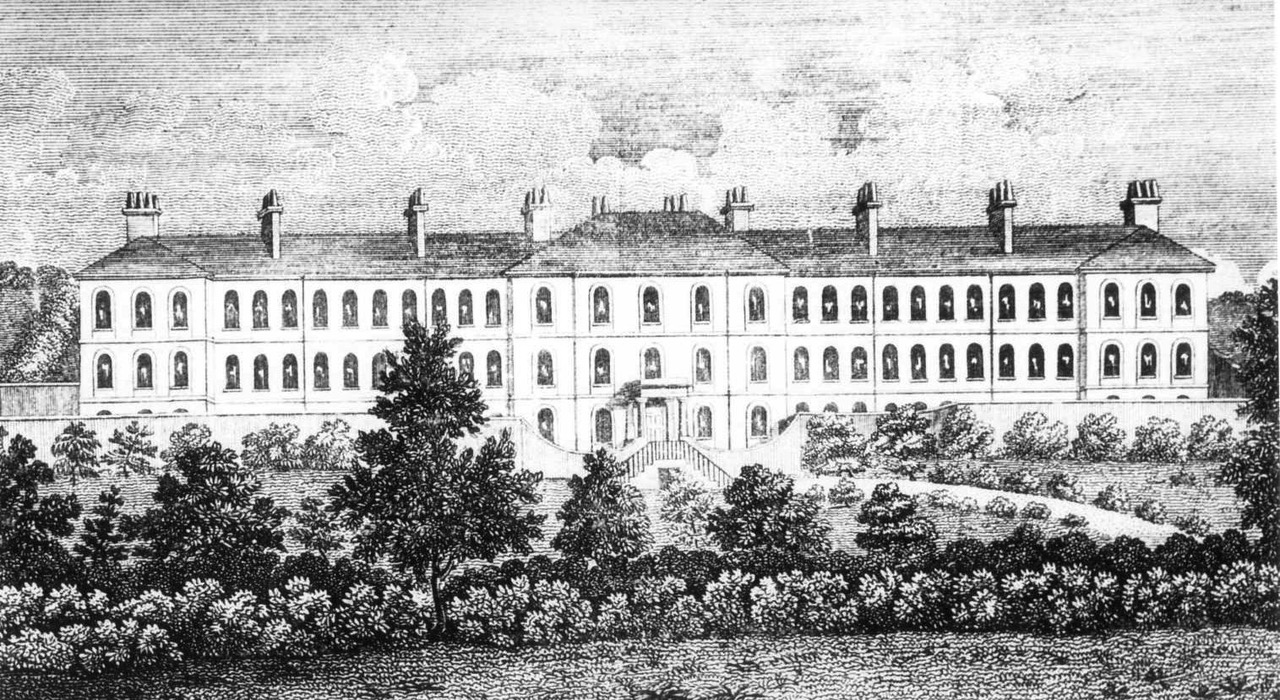

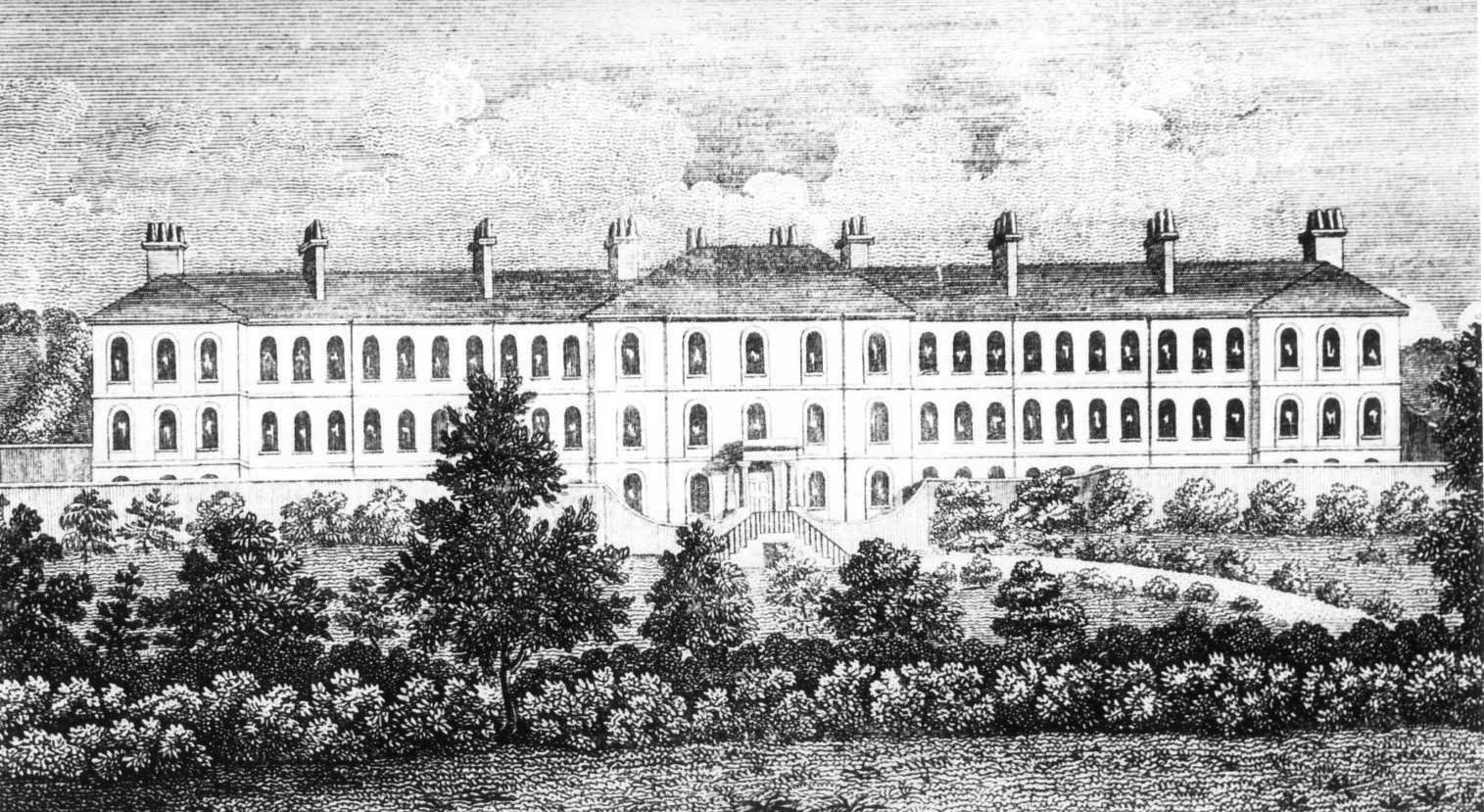

Patients at the Sneinton Asylum would have experienced a variety of treatments, ranging from therapeutic and progressive to experimental and outdated practices. The site of the asylum was intended to provide a calming and peaceful location, surrounded by green spaces. The site is now King Edwatd Park, which reflects the original intention, providing a communal park and greens paces for the local community,

Likwise it was intended that restraint and more violent treatments which were previously used, would not be practiced in the Sneinton Asylum. However, in the thirtieth annual report for the asylum Blake and Powell (asylum surgeon and physician) noted that whilst they always tried to minimise restraint, there were still times when restraint was necessary. This was flying in the face of Dr Gardiner Hill at the Lincoln Lunatic Asylum who espoused “no restraint" in asylums.

Of the early treatments we know were in practice at the Sneinton Asylum, hardly any would be used to treat mental illness or disability today. These include emetics, purges, blood-letting and blistering. From 1827-30 the revolving chair was used, in which a patient was hurled round at 100 revs. per minute, resulting in vomiting, evacuation and even unconsciousness. Alongside this, we know that patients also experienced spending time outdoors and gardening in allotments, visits from friends, reading and as mentioned in the 1846 annual report a Ball at the Asylum in a 'Large and commodious room fitted out with flowers and evergreens', which 'Began with glee singing. One patient gave recitations' and also included 'Country dancing'.

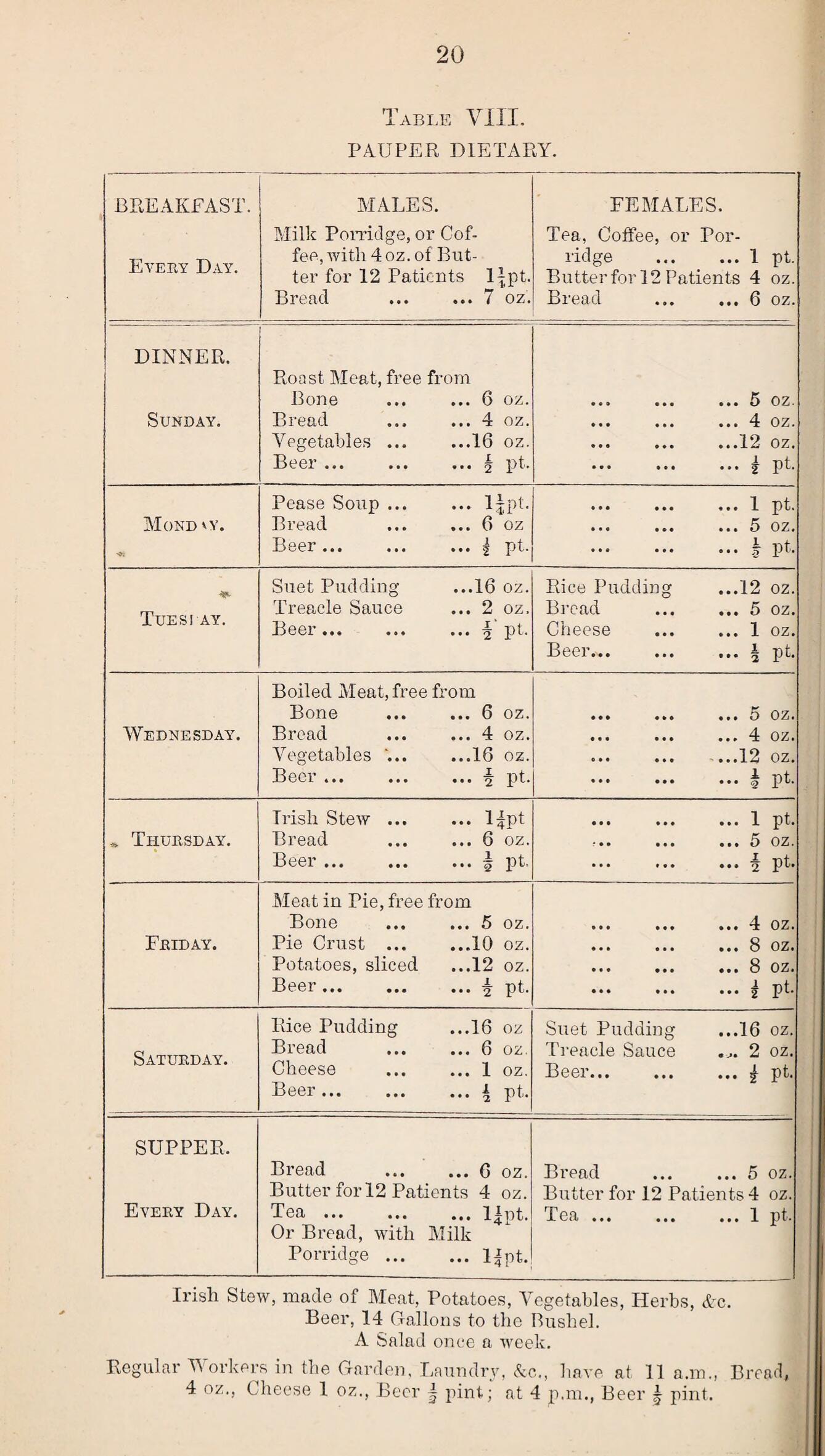

The diet of patients was limited, and the class of the patient determined what their meals were.The image below details the diet of the 'pauper' or poorest patients.

Fifth annual report of the state of the United Lunatic Asylum for the county and borough of Nottingham; and the fiftieth of the original institution, formerly the General Lunatic Asylum : year 1860.

GENDER

During the 1800's, women of all classes were not afforded the same rights as men. Although your class had an incredible impact on your life experience, and the patient experience if entered into an asylum, women were considered 'second class citizens' to their male counterparts.

For the poorest women and girls in society there was very limited support, from both the government and authorities and the public. Society took a low view of 'pauper' women, especially following the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which implemented harsher rules around dealing with 'Mothers of illegitemate children', stating they should recieve much less support and that fathers would no longer be traced by authorities, in order to provide support to their children. Social support offred by parishes was also reduced dramatically, meaning that the workhouses should serve as the only option for the poor in this time.

Set against the backdrop of a time in which women had social pressures to marry, give birth, then be good wives and mothers, with little to no prospects of working, whether working or middle class - women could find themselves admitted to asylums for a number of reasons with very little questioning or evidence at times.

The physiognomy of mental diseases / [Sir Alexander Morison].. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

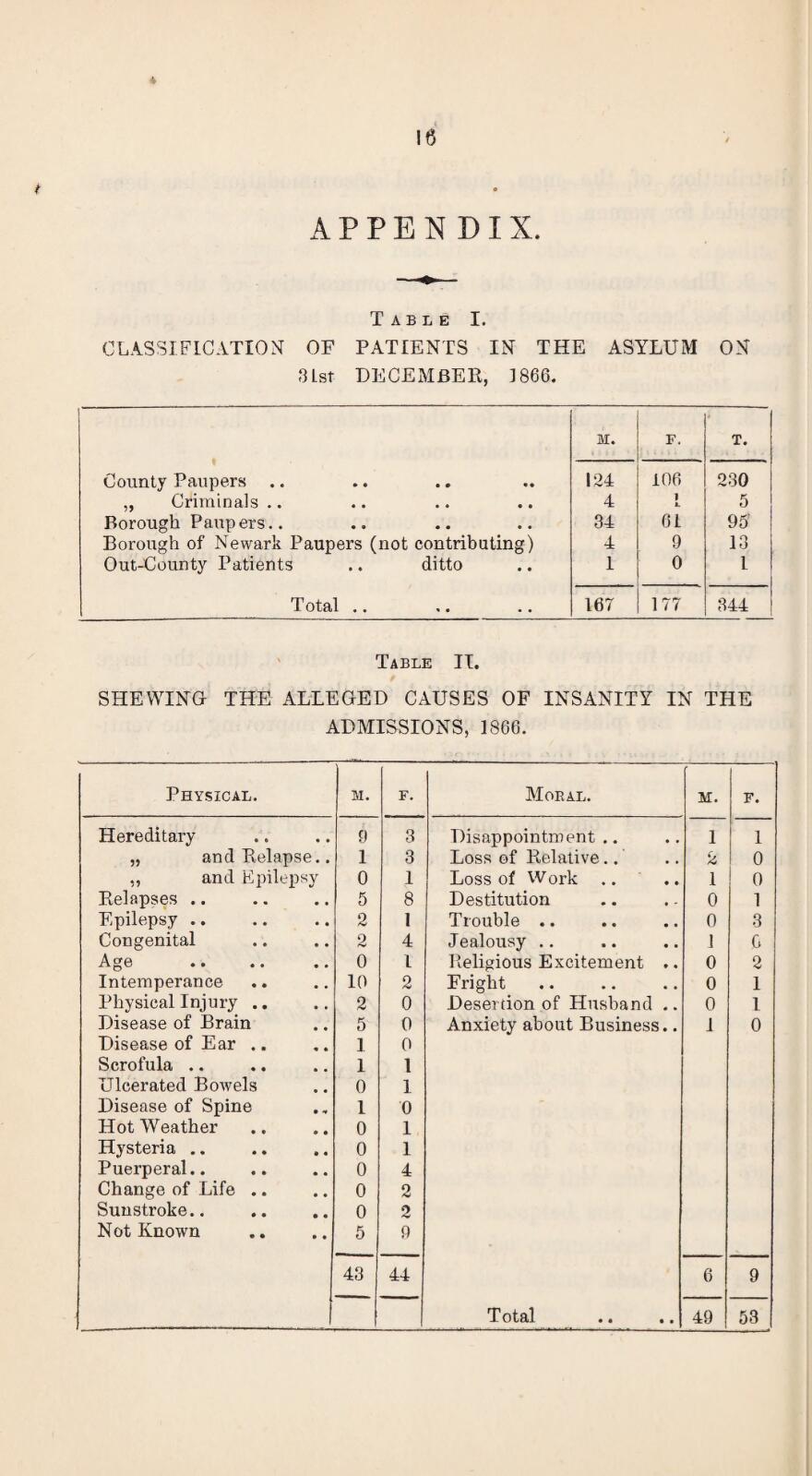

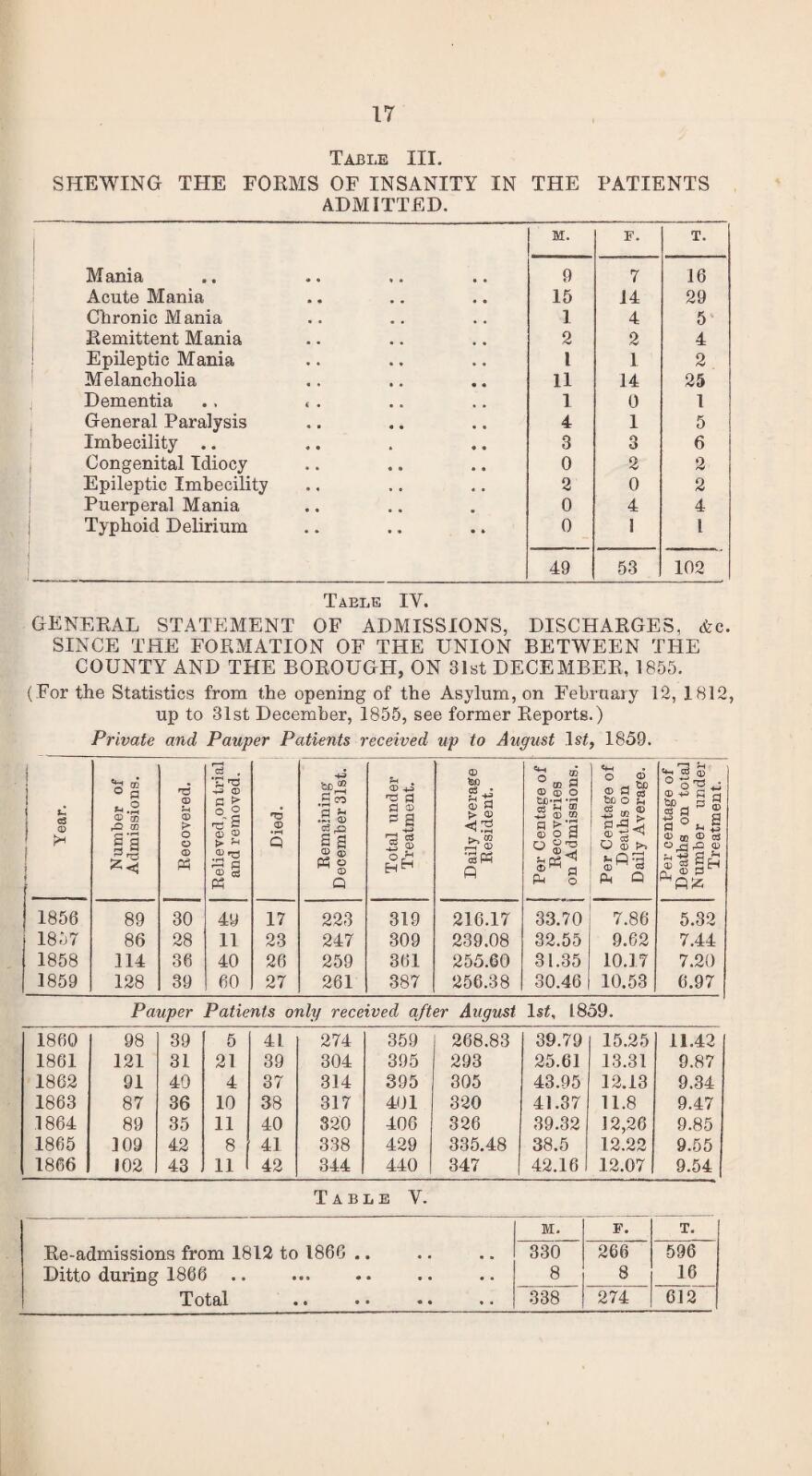

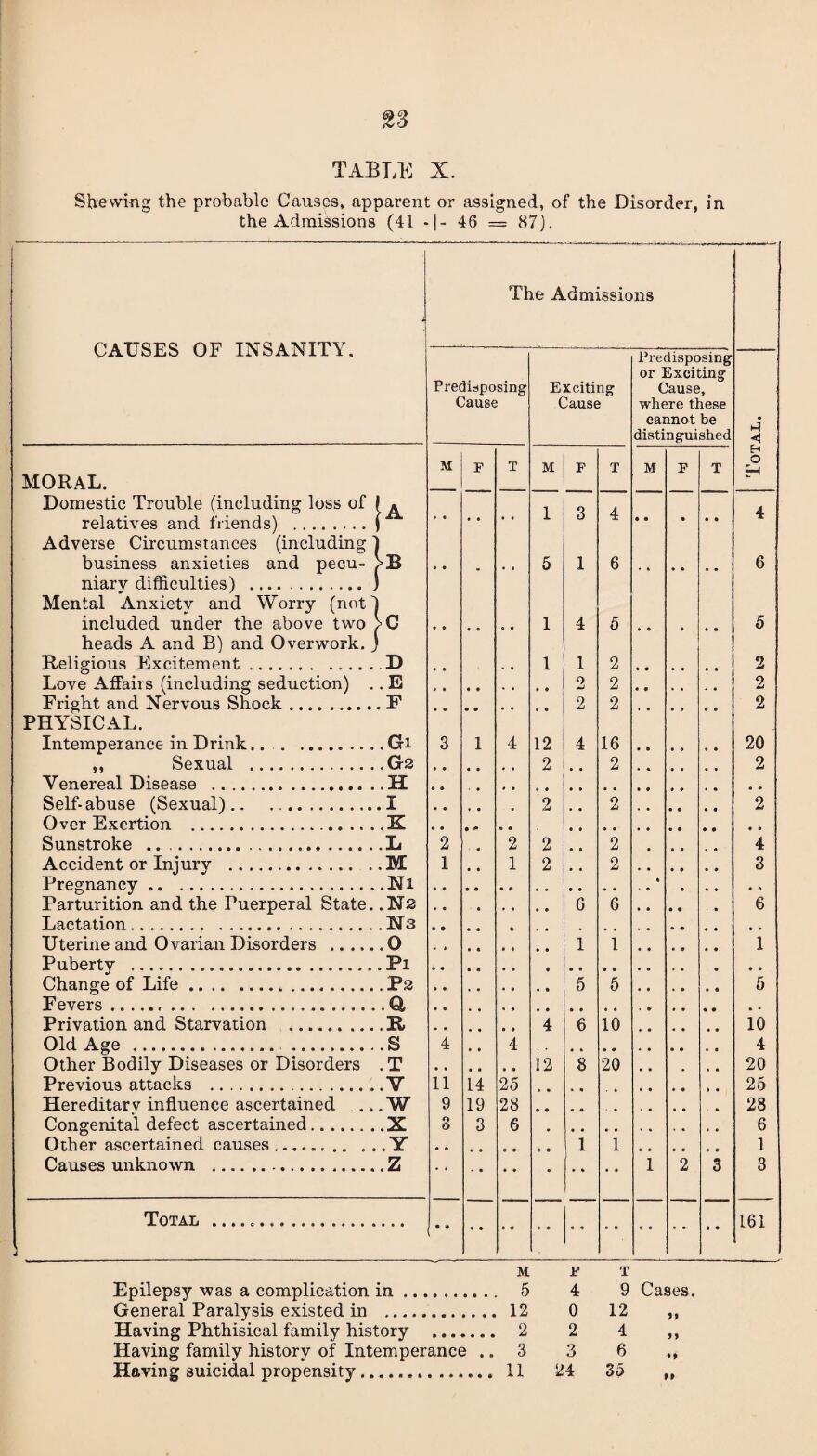

These images are taken from the 11th, 13th and 14th annual reports (1885-1888) for the Sneinton Asylum, they highlight the high numbers of women admitted to the asylum and the reasons they were deemed 'lunatics' or 'insane'.

Examples where we see higher cases of women and of these are Puerperal or Parturition (which means pregnancy and child birth related), Change of life, Domestic Trouble, Intemperance in drink/sex (Alcohol and sex related) Uterine & Ovarian (directly related to female reproductive organs), Mental Anxiety and Worry and Hysteria.

In the 19th century the effects of pregnancy and childbirth on mental health were not understood in the same way that we understand them today. Common mental health problems which today we understand as antenatal, postnatal and perinatal depression, anxiety and postpartum psychosis, were not fully understood, and as a result were classed as 'Causes for Insanity'. The above image is from a series by Alexander Morison, depicting puerperal insanity or insanity at childbirth. The patient is wearing restraints and gloves, which were applied to stop self harm or masturbation.

Hysteria came into the public consciousness in the late 19th century, following the medical practices and teachings of Jean-Martin Charcot from 1880 onwards. From the greek word 'hystera' meaning 'uterus', hysteria was considered a completely female illness. Charcot beleived hysteria to be a neurological disorder linked to the nervous system, which produced symptoms such as convulsions, fainting, numbness, paralysis and attacks of emotion and nervousness. Charcot linked it closely with epilepsy and symptoms which they shared. Causing such varied symptoms, often meant that women could be treated for and instituionlised very easily under the umbrella term of Hysteria, especially when no other diagnosis could be given. However, in the 21st century with advancements in medicine and understanding of mental health and illness, such extreme responses would not be administered.

Common treatments used for hysteria were the 'rest cure', which meant women were forced to stay in bed, fed fatty foods, massaged and sometimes electro shocked. Pelvic massage was also administered, which often used elecronic devices on female genatalia to create stimulation.

CLASS

Patient experience of asylums was greatly influenced by class, and this reflected in the class of patient you were deemed upon entering the asylum.

First Class were the private patients, that could pay for their treatment and all costs of their stay in the asylum.

Second Class were those who were not paupers but could not pay the full fee so were supported by the funds raised by subscribers; these were people that privately funded the asylum.

The Third Class were the 'paupers' whose fees were paid by the Poor Law Guardian (the state).

Inequality in the treatment of the patients admitted was reflective of the society in which the Sneinton Asylum was built, in 1812 when the asylum opened many of the poorest people in Nottingham were at high risk entering of Workhouses, prisons and asylums.

The activities that patients and treatments that patients experienced were heavily influenced by their class, with often poorer patients being given labor and manual tasks to do, in contrast with the more creative and leisurely activities of wealthier private patients.

The second annual report of the state of the lunatic asylum for the County of Nottingham, and the sixty-sixth of the original institution, formerly the General Lunatic Asylum, 1876.

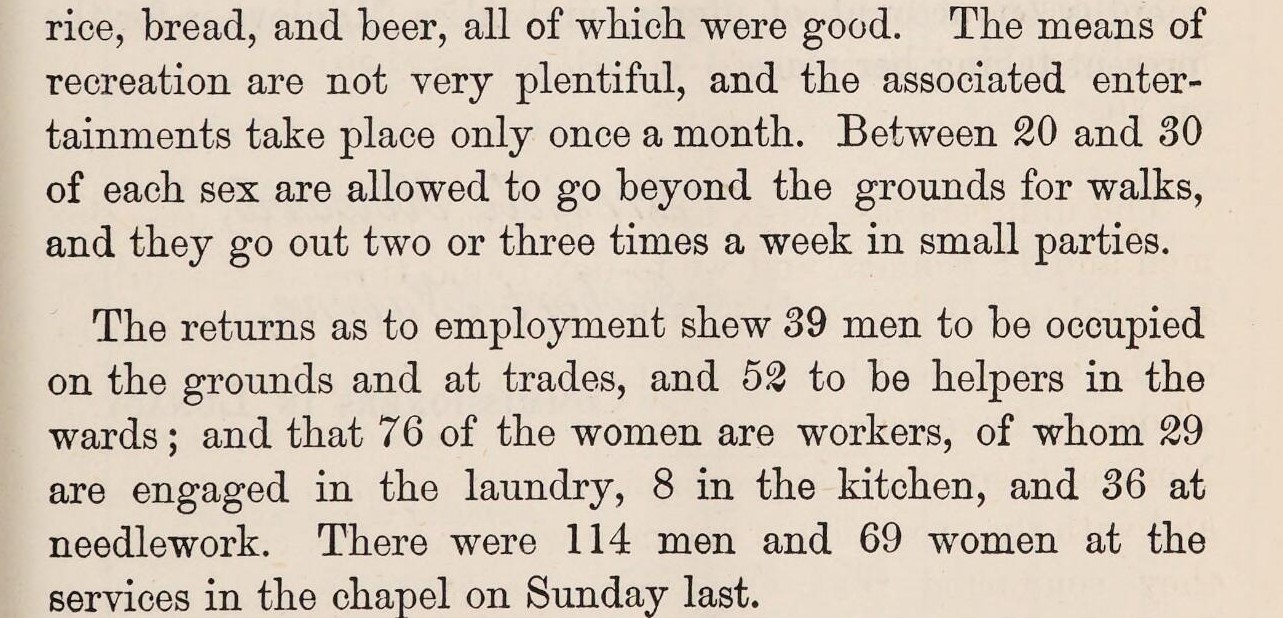

Extract on recreation and employment of patients from The nineteenth annual report of the state of the United Lunatic Asylum for the county and borough of Nottingham, and the sixty-fourth of the original institution, formerly the General Lunatic Asylum, 1874

London labour and the London poor : a cyclopaedia of the condition and earnings of those that will work, those that cannot work, and those that will not work. / by Henry Mayhew.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

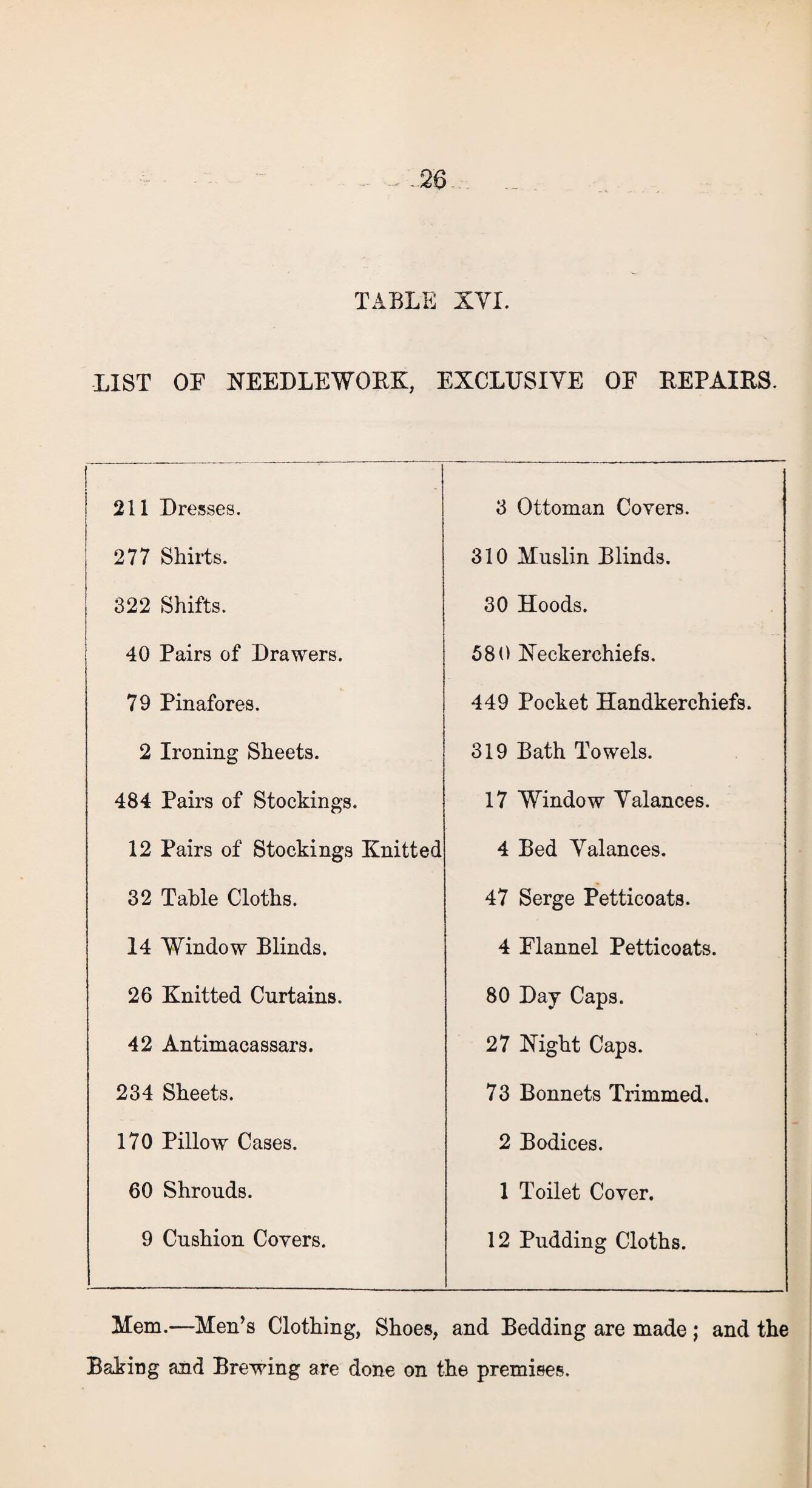

The table to the right is from the Sixty Sixth annual report (1877) shows the needlework activity conducted by (predominently female) patients at the Sneinton Asylum. As noted at the bottom of the table baking and brewing of beer is all done on site. In the annual reports we can see that employment is listed as part of the treatment of patients, however these labour intensive tasks would not have fallen on the first class patients for whom this form of work was unfamiliar.

In an earlier report (1840)we see a more detailed account of the work patients were doing:

Males:

Outdoor Work – 29

Helpers in house and galleries 19

Working in Stocking Frames 3

In Laundry 1

In turner’s shop 2

As saddler 1

55

Females

Plain and Fancy Needlework 29

Scaming stockings 5

In laundry 9

Helpers in wards and house 10

Knitting stockings 2

Picking coir, hair or wool 12

66

The effects of such inequality, both societally and as patients, on the ‘lower class’ or ‘pauper’ patients is highlighted in an excerpt from the fiftieth annual report (1860), which describes the death rate at the asylum.

The deaths were 41, 0r 15.25% on the mean number resident. A higher rate than heretofore was expected in consequence of the receptions into the Asylum being limited to Pauper Lunatics. They undergo greater privations than Private Patients, and are for the most part admitted in an enfeebled state of health. There is no exclusion of the Moribund, the Paralitic, the Epileptic or the Incurable; and the friends have not the power of discharging them at will, as in the case of those who are in a better position, who are not unfrequently removed to prevent their dying under confinement.’

The ways in which patients were admitted following the 1828 Madhouse Act, was very different based on class. The commitment of Private Patients required a certificate from 2 medical men, which could be recommended by family and friends.

Commitment of Pauper Patients required a certificate signed by 2 magistrates or an overseer of the poor, and a clergyman of the parish along with a signed medical certificate.

Private patients were therefore allowed to be taken out by friends and family, whereas this privilege was rarely afforded to pauper patients, especially in times of illness should they need extensive medical treatment, as this required more money.

However, some argue that pauper patients were at less risk from inappropriate confinement, in comparison to wealthy patients. It was common for the family and friends of wealthy patients to claim they were lunatics, with the intent of inheriting or seizing their assets.

It was noted in the initial research conducted by our team that information relating directly to the treatment of ‘homosexual’ people in asylums 19th Century Britain, was incredibly difficult to find. Following discussions with academics and local researchers we began to understand that the lack of information on these histories, reflected the period in which we were examining.

The last execution for ‘sodomy’ in the UK, took place in 1835 after James Pratt and John Smith were arrested for ‘an unnatural crime’ (London Standard, Monday 23rd November, 1835).

At the time we can see from records that they were indicted for ‘buggery’, however when public records or articles refer to these crimes they were often referred to as ‘unnamed offences’, ‘an unnatural crime’, ‘unnatural offences’ or a ‘nameless offence’, suggesting that societally these acts were considered so unspeakable and criminal that naming them would be too shocking for the public. Other codes in such as (b) for buggery or (s) for sodomy, in place of the offensive words, can be found in newspaper articles.

The term unnatural offences dates as far back as 1533, when Henry VIII passed a law stating that it was a criminal offence to engage in anal sex or bestiality. The two crimes were then inseparable for many years, referred to in the period we are exploring in the Offences against the Person Act 1861:

Unnatural Offences

Sodomy and Bestiality.

Whosoever shall be convicted of the abominable Crime of Buggery, committed either with Mankind or with any Animal, shall be liable, at the Discretion of the Court, to be kept in Penal Servitude for Life or for any Term not less than Ten Years.

These codes help us only in that we can find evidence of these unnamed crimes, however this becomes more difficult following the end of capital punishment, when attempting to find records of LGBTQ+ people that were institutionalised. With the two crimes listed together under ‘Unnatural Offences’ it is also difficult, unless stated, to decipher whether it was an act of ‘sodomy’ or ‘bestiality’.

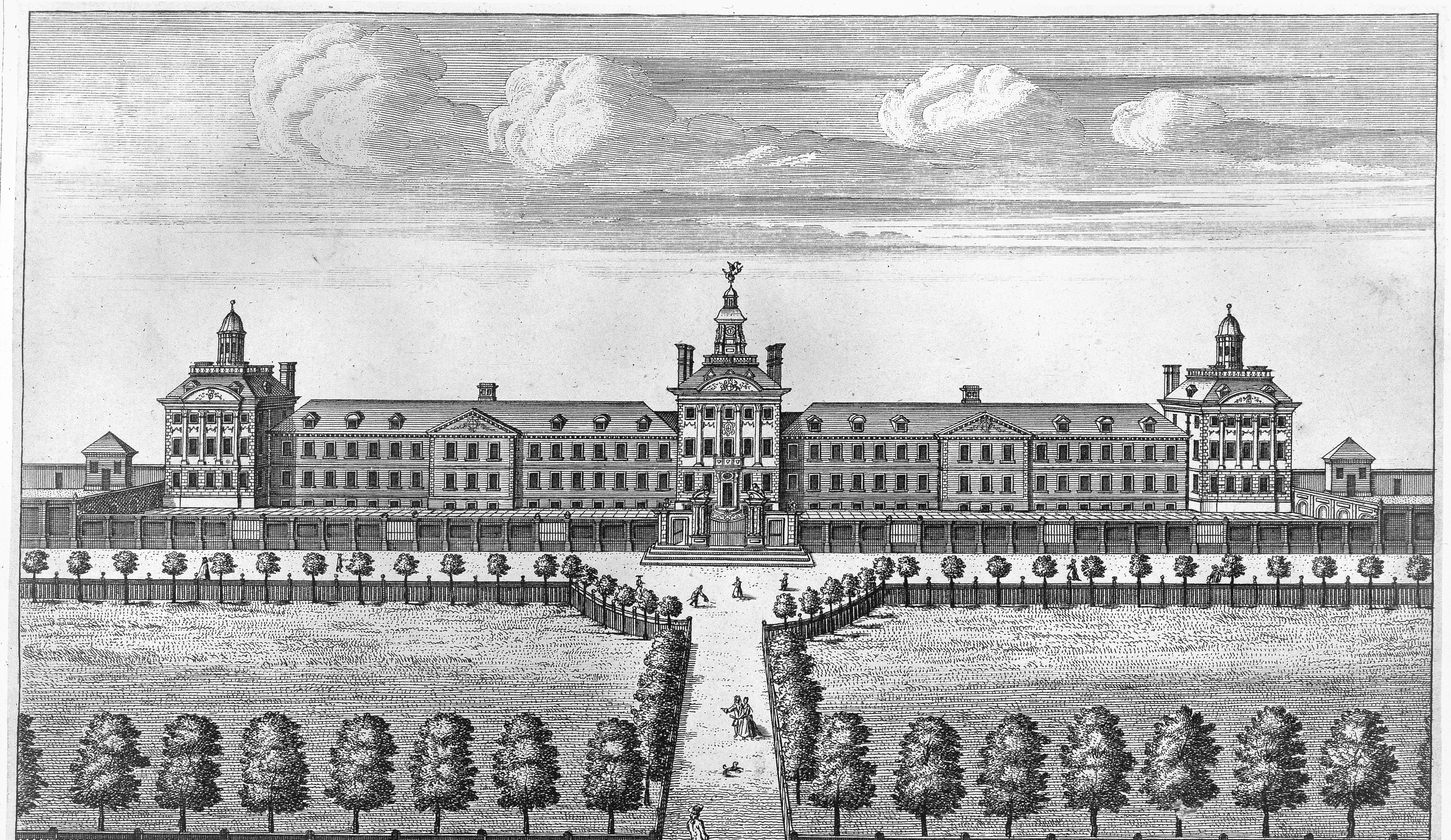

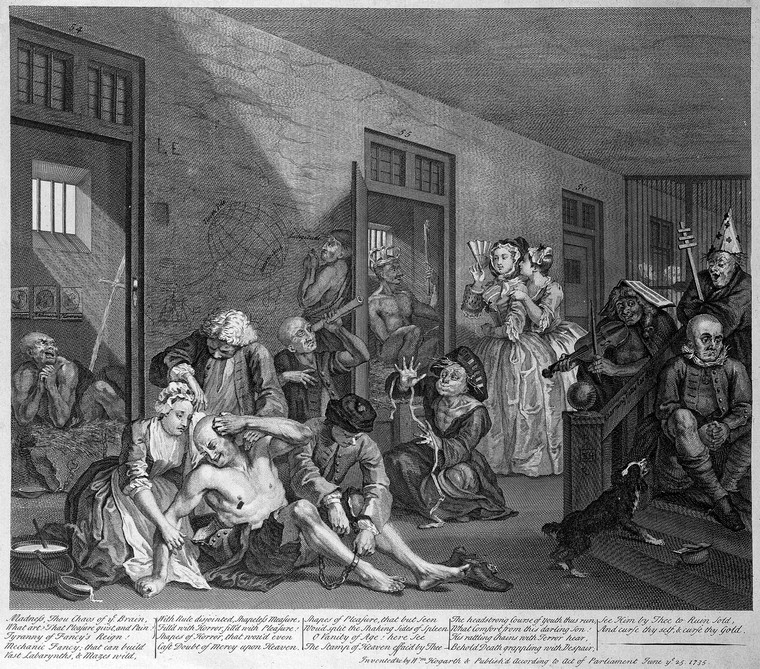

Hogarth's The Rake's Progress; scene at Bedlam. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Rictor Norton (Ed.), "The Last Men Executed for Sodomy in England, 1835", Homosexuality in Nineteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook, 12 September 2014

As Dominic Janes, one of our researchers with a specialism in this area, discusses when examining ‘Criminal Lunatic’ case records of Broadmoor and Bethlem asylums;

'Many of these books were printed with a list of possible crimes in order of (or, at least, in the order of the contemporary perception of)seriousness, ranging from murder at one extreme to vagrancy at the other. “Unnatural offences”were placed as less serious than murder and rape but more serious than sedition and assault. Accordingly, criminal lunatics were categorized, and thus to a degree conceptualized, in the medical environment by reference

to legal offenses rather than by diagnoses. This creates a particular complication for the study of homosexual behavior insofar as the records are not always clear in distinguishing between sexual acts between men and cases of bestiality (which were also frequently referred to as sodomy); however, thirteen cases clearly, or almost certainly, referred to the former. In addition, details of a further eight individuals classified under the category of “unnatural acts” could not be checked either because the file was missing or because of the closure rule of one hundred years from the death of the

patient that is applied to these records.

Only small numbers of those convicted for homosexual offenses found their way into the main institutions of the criminal lunacy system during the nineteenth century. The level of detail provided by the case notes is not always impressive, nor can they be matched conveniently with more

than very cursory records of trials. Therefore, the quality of the surviving evidence does not allow the researcher to put together a detailed record of precisely why these sodomites and not others were found not guilty by reason of insanity. Still, these materials, written by the medical staff, do give considerable insights into medical attitudes toward those understood to be both sodomites and suffering from mental illness.'

(Dominic Janes Journal of the History of Sexuality, Volume 23, Number 1, January 2014, pp. 79-95 (Article)