A HISTORY OF NOTTINGHAM ASYLUMS

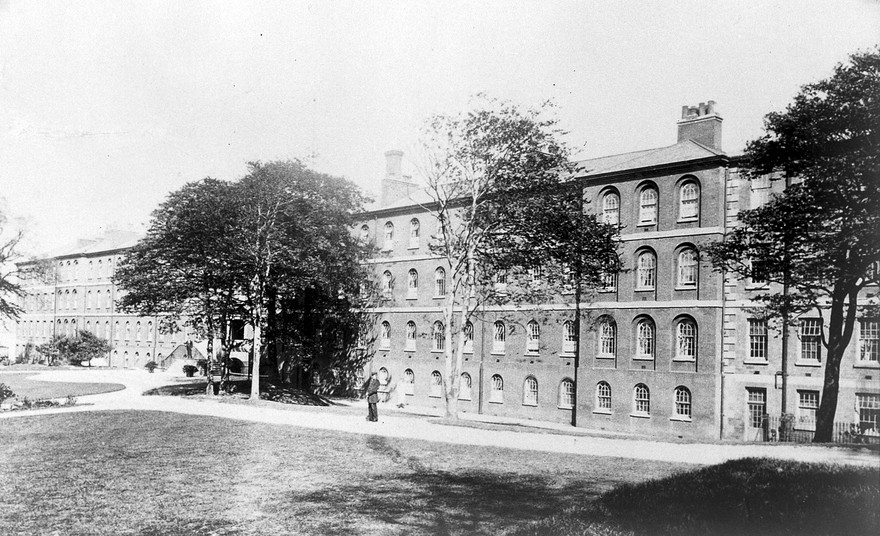

Sneinton Asylum/Nottingham General Lunatic Asylum 1812-1902

The Nottingham General Lunatic Asylum opened its doors in 1812, taking patients from varying classes and backgrounds. The initial intention of the asylum was that all patients were treated kindly and respectfully, following the methods used by Quakers at asylums in York and Bristol. Dr John Storer, physician to the General Hospital, was the leading figure in raising funds and ensuring the asylum was built. He worked closely with Rev JT Becher of Southwell who had been instrumental in the development of the Southwell Workhouse and was familiar with working with ‘paupers’ there.

Nottingham Borough Surveyor Edward Staveley and architect Richard Ingleman, were responsible for designing the asylum, taking inspiration from the Quaker hospitals in York and Bristol.

Although restraint was used in the asylum, alongside other treatments which didn’t align with the initial humane approach that was wanted, many patients had jobs within the asylum.

Taken from the '1840 Annual Report – Thirtieth Report 12 December 1840'

Males:

Outdoor Work – 29

Helpers in house and galleries 19

Working in Stocking Frames 3

In Laundry 1

In turner’s shop 2

As saddler 1

55

Females

Plain and Fancy Needlework 29

Scaming stockings 5

In laundry 9

Helpers in wards and house 10

Knitting stockings 2

Picking coir, hair or wool 12

66

However due to the constant issue of overcrowding, the decision was taken by the Charity to establish a new lunatic hospital for non-pauper patients. The demands on the asylum had increased and it had to be decided to extend the present Asylum or create a new establishment. The Coppice, designed by T.C Hine was built and opened in August 1859. This new asylum was only for first- and second-class patients, with the pauper patients remaining at Sneinton.

Broom House Retreat for Lunatics 1848-1862

An application was made to the magistrates for a licence to keep a house for the reception of lunatics in Mansfield. The application was made by Nottingham Physician, Dr Thomas Wilson, who was a graduate of the University of St Andrews. His application was approved by Dr Booth Eddison. Booth Edison eventually took on the asylum. In the 1851 census, the Broom House Retreat for Lunatics is recorded at Belvidere Street. Thomas Wilson resided there with his wife, Elizabeth and his son, Edward. There were eight residents, five men and three women, ranging in ages from 20 to 60. There was a resident Matron.

Later in 1851 he made an application for another licence for a private home for five female patients. Questions were raised about Dr Wilson. It was stated that he had allowed a patient at Broom House to apply for a marriage licence. Dr Wilson claimed that the person was semi-idiotic and about to be discharged as recovered. It was noted that the Commissioners in Lunacy knew about the case and had not felt it necessary to take action.

After numerous licence holders, the licence for the asylum was passed onto Booth Edison and his family.

The Broom House Retreat had begun as a mixed house but the last male, Joseph Beardmore was discharged on 10 January 1852. From that time onwards the home was exclusively for women.

The Asylum was said to be set in “pleasant grounds with every convenience for the classification of patients of the higher and middle classes.” There was the facility for Carriage and Garden exercises.

After Booth Eddison’s death, his wife continued the asylum with Miss Stevenson as the Superintendent but by 1862 the house was up for sale and Mrs Eddison died in 1863.

The last patient to be discharged was Isabella Mansfield on 19 November 1862.

Coppice Hospital 1859-1985

The Coppice was built as a response to the disillusion of the agreement between the County and Borough of Nottingham and the charitable subscribers who helped fund the Sneinton Asylum. With Sneinton solely used as the site for pauper patients, new accommodation was sought for the private patients. A hilltop area in St Anns was selected as the site, known as The Coppice and part of the Coppice Farm was later purchased. Popular architect Thomas Chambers Hine was selected to design the building.

The Coppice opened in 1859, with over half of the Sneinton Asylum patients relocating by the end of the year. The conditions of those moved from Sneinton to Coppice were improved greatly, with this asylum providing only private and the most charitable of cases with a more comfortable environment in which to recover, with pauper patients excluded.

By 1880 plans were made to extend the building, with G.T Hine, son of T.C Hine, leading on the design. This added capacity enabled patients outside of the county to be admitted. G.T Hine was also the architect on the Nottingham Borough Asylum at Mappereley in the late 1880’s, which had also separated from Sneinton.

The Coppice continued as a mental hospital until 1985, undergoing various developments in response to the development of the NHS and economic factors, eventually being closed, sold and redeveloped into housing.

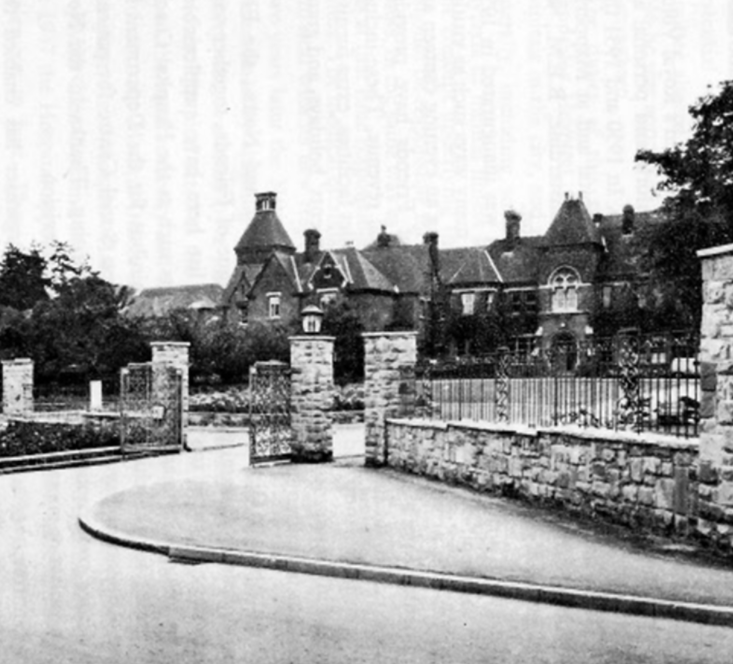

Mapperley Hospital 1880 - 1994

Responding to the high demand for spaces in asylums, it was decided in 1874 that a new purpose built asylum was to be built in Nottingham. The Mapperley asylum was designed by Nottingham’s George Thomas Hine, son of Thomas Chambers Hine (who had previously designed The Coppice). George Hine would go on to be the UK’s most noted asylum architect, completing 14 asylums in total.

Mapperley opened on 3 August 1880, with DR Evan Powell as the Medical Superintendant. It was designed for 280 patients, and after taking 246 from Leicester Borough Asylum and the Derby County Asylum, as well as those from Sneinton and the Nottingham Workshouse, it was full by the end of its first year.

Mapperley strove for self sufficiency with its own farms, bakery, library, kitchens, plumbers, carpenters, upholstery rooms, tailors, sewing rooms, laundry. Electricity was introduced somewhat late in 1924, which then allowed for wireless broadcasts to be played throughout the wards and cinema equipment was installed in 1927.

Dr Duncan MacMillan was the Superintendent from 1941 – 1966, in this time he was thought to revolutionise the way the establishment was ran and the treatment of its patients. He worked closely with patients to change the ways they viewed themselves and equipping them with tools for surviving when they left the institution. Wards were refurbished, seclusion abandoned and padded cells removed and he played a huge role in redefining what a mental hospital could be. Patient numbers declined dramatically in the 1980’s and Mapperley was closed in December 1994.

Saxondale Hospital 1902-1988

The new Nottinghamshire County Asylum, opened in July 1902, was planned and developed to replace the Sneinton asylum. The Sneinton asylum was outdated and the building dilapidated by this point so was closed for good.

The site, which was located in Radcliffe on Trent, was designed by the firm Hooley and Sandar, and the large estate could house up to 450 patients.

World War I brought about the requirement to vacate a number of civilian asylums for military usage and Saxondale ended up taking some of Wadsley Park Asylum’s inmates. As such, the majority of the war passed with Radcliffe accommodating Wadsley inmates in addition to their own. All were vacated by the summer of 1918 and it also became a war hospital so the inmates were again spread across the remaining receiving hospitals.The role of the asylum as the Notts County War Hospital was to be short lived with the cessation of hostilities and reverted to civilian use after August 1919.

With the reconfiguration and merger of the two mental health hospital management committees for Nottingham in 1970, Saxondale joined with Mapperley and Aston Hall, both former Nottingham City institutions, as well as The Coppice Hospital under the Trent Vale HMC. The services of Saxondale, Mapperley and The Coppice had last been managed together as long ago as 1855 when the union forming the committee for Sneinton Asylum split for the first time.

The hospital was investigated during 1981 as part of an inquiry into untoward deaths and the following year was once again merged with Mapperley in 1982. Closure of Saxondale was announced in the autumn of 1983. This resulted from a number of factors including; the location of the hospital and its comparable isolation, the development of outpatient services and community care, the gradual reduction of the long-stay inpatient population, and the creation of new facilities within the district general hospitals of the health authorities serving the area. Mapperley, being more conveniently located for the city and transport links, had spare capacity which could absorb some of Saxondale’s wards, services and patients. Services were then correspondingly reduced at Saxondale as new units in the Central Nottinghamshire, Nottingham and Bassetlaw DHA areas came into being and nurse training was transferred to the Queens Medical Centre and Mapperley sites. Once the last of the services vacated the complex in 1988 the hospital was finally closed after only 86 years of use, four years less than it’s predecessor at Sneinton asylum.

Images courtesy of COUNTY ASYLUMS and Wellcome Collection.

Legislation, Reports and Committees Timeline

1744 – Vagrancy Act – section 20 – Allowed two or more justices of the peace authorised by warrant to direct the constables, church wardens and overseers of the poor to apprehend them and have them safely detained, and if their ‘lunacy’ or ‘madness’ required, for them to be chained.

1774 – The Act for Regulating Private Madhouses – Outside of

London, licensing of madhouses was to done justices

at the Quarter Session. Two justices and a physician

were to be nominated at the Quarter Sessions to visit

and make reports.

1800 – Criminal Lunatics Act – The Act did not direct where

these people were to be housed nor any machinery

by which they might ultimately be released.

1806 – Returns of pauper and criminal lunatics -

Nottinghamshire said it only had 35 pauper lunatics

for whom provision was needed and no criminal

lunatics.

1807 – Select Committee to enquire into the State of Criminal

and Pauper Lunatics in England and Wales.

1808 – County Asylums Act – First Asylum to be constructed

under the Act was Nottingham.

1815 – Amending Act – issues of admission, certification and

discharge. Overseers of the poor to furnish returns of

all lunatics and idiots within their parishes to the

justices on request.

1815/16 – Select Committee – Mr Becher reported on the

Nottingham Asylum.

1827 – Report on the Condition of Pauper Lunatics in the

Metropolis.

1828 – Madhouse Act (Gordon Act) – Secretary of State for

the Home Department acquired power to send any

visitor to inspect an asylum. In the provinces two

justices and a medical visitor appointed at the

Quarter Sessions were to visit each house four times

a year. Did this apply to Nottingham which was part

subscription hospital.

1832 – Commissioners for Metropolitan Madhouses

must include at least two barristers. The inspectorate

was removed from the Secretary of State to the Lord

Chancellor. County Asylums continued to be under

under the supervisory authority of the Secretary of

State.

1834 – Poor Law Amendment Act. Under the classifications o

inmates there is no mention of lunatics or idiots. There

is however mention in Section 45 “nothing in this Act

shall authorise the detention in any workhouse of any

dangerous Lunatic, insane Person, or Idiot for any

longer period than 14 days; and every person wilfully

detaining in any Workhouse an such Lunatic, insane

person or Idiot for more than 14 days shall be deemed

guilty of a misdemeanour.” The word “dangerous”

became critical.

1838 – Select Committee on the Poor Law Amendment Act

1838. Discussion about whether asylums should come

under jurisdiction of Poor Law Board.

1841 – 4th November – First Annual meeting of the

Association of Medical Officers for the Insane,

held in at the Nottingham Asylum, where Dr Andrew

Blake, visiting physician to the Nottingham Asylum

took the chair. There was a thorough inspection of the

Asylum. (At the inaugural meeting in July 1841 in

Gloucester Asylum, Mr Powell the resident medical

Superintendent of the Nottingham asylum was

present.)

1842 - Metropolitan Commissioners empowered to carry out

inspection of all

asylums in he country. They were to be visited twice a year

unless Lord Chancellor deemed less frequent visits. To

operate for three years. Number of Commissioners increased.

There were to be 15-20, of whom four were legal Commissioners

and six or seven physicians or surgeons. Masters in Lunacy

1844 – The Report of the Metropolitan Commissioners – includes reports

on County Asylums including Nottingham. Report is on

Wellcome website. “Since the new Poor Law came into

operation, an increased reluctance has been exhibited on the

part of the parish authorities to send their poor to an asylum,

and the patients frequently come in a very debilitated and

exhausted state.”

1845 Lunatic Asylums Act - New Lunacy Commissioners

appointed. Included five laymen, three medical and

three legal commissioner. Certification. Records.

1845 – Alleged Lunatics Friend Society formed. Concerned over

the liberty of the subject.

1851 – Census – Asks if person is deaf, dumb, blind or lunatic. Return

made of those in asylums.

1853 – The Amending Acts

1. Related to private asylums and subscription hospitals

2. Related to county (now public) asylums and the admission

of patients to them. Also about how asylums might be set

up two counties or combination of public funding and

privated subscription. Nottingham was well ahead of the

game!

3. Chancery Lunatics whose families were concerned about

the control over money. Attempt to lessen legal expenses

by allowing an inquisition by a Master in Lunacy alone in

cases where the petition was un-apposed.

1855 - Free Schools Bill allowed the free education for pauper children

in England and Wales except for those who were deaf, dumb, blind, lunatics or criminals.

1859 – Select Committee

1862 – Education of Pauper Education Act. Empowered Guardians to

fund children in institutions for blind, deaf, lame and idiotic

persons.

1870 – Education Act – the beginning of universal education. As time progressed authorities realised that not all children

progress at the same rate. The Board of Guardians was required to send pauper deaf-and-dumb (and blind) children, under the age of 14 years, to a suitable institution for their education. The education of deaf and dumb children became compulsory in 1893.

1874 – Grant-in Aid of Pauper Lunatics. From the Consolidated Fund, 4s

a head was paid for each pauper removed to an asylum. This

an incentive for Poor Law Guardians to remove paupers from

the workhouse into an asylum for curative treatment.

1877 – Select Committee (Dillwyn’s Committee)

1877 – Sub-Committee of the Charity Organisation Society

1886 – Idiots Act This was intended to give "... facilities for the care, education, and training of Idiots and Imbeciles".

The Act made the distinction between "lunatics", "idiots" and "Imbeciles" for the purpose of making entry into education

establishments easier and for defining the ways they were cared for.

1889 – Royal Commission – Report on the Blind, Deaf and Dumb and

others. (Egerton)

1890 – The Lunacy Act - This formed the basis of mental health law in England and Wales from 1890 until 1959.

It placed an obligation on local authorities to maintain institutions for the mentally ill.

1898 – Education Department – Report of the Departmental

Committee on Defective and Epileptic Children.

Defining of which disabled children should receive education

and which should not. Medical dominance in decisions. Those

with most severe disabilities had to wait until 1970.